Investing In Fine Wine: The Do’s And Don’ts—Part II

Lewis Chester DipWSET on regional variation in potential returns.

© Saison d'Or

If you want to see which fine wine estates professionals think are the best in the world, I implore you to download the latest Gerard Basset Global Fine Wine Report (which forms the basis of The Golden Vines Awards, aka ‘The Oscars of Fine Wine’). Last year, 442 fine wine professionals from 55 countries, with an average experience of more than 18 years in the industry, participated in the report, making it by far and away the world’s largest fine wine poll.*

For now, let’s break down investment potential region by region.

Apart from a few smaller-production and extremely sought-after wines that generally are only available on allocation (you have to be a well-established fine wine buyer to be on the list) such as Château Petrus, Château Le Pin, and Château Lafleur (all on the Right Bank of Bordeaux), the investment-grade wines are the big five First Growths of the Left Bank: Château Haut-Brion, Château Lafite Rothschild, Château Latour, Château Margaux, and Château Mouton Rothschild.

Château Cos d’Estournel, Bourdeaux

There are others which are investment grade, such as Château Montrose, Château Cos d’Estournel, Château Pichon Lalonde, Château Pichon Baron, Château Leoville Las Cases, and at least another 15 names across the left and right banks of Bordeaux. In building our portfolio, we have to have some of these top Bordeaux wines. In a handful of instances, we probably want to own their ‘second wines’ as well, such as Les Forts de Latour, Carruades de Lafite and Pavillon Rouge du Château Margaux.

It’s worth noting here that owning the best vintages is not necessarily an indicator of investment performance as it was in the past: the likely reason behind this is that, in a social media-obsessed society where consumers take their lead from what their favorite Hollywood or NBA star is drinking, the focus is on the label, and not the quality of the vintage.

The problem with being too top-heavy with Bordeaux is that if Bordeaux prices stay stuck-in-the-mud and/or drinkers have fallen out of love with these wines, your returns are going to be poor. You might not lose much money over time, but you probably will not make much.

Burgundy is the most in favor, sought-after and high-returning fine wine region in the world today. There is a strong argument that this will continue due to the very small quantities of top wines made by Burgundy domaines and the low yielding harvests that the region has faced in recent years, as climate change has impacted Burgundy more severely than many other top fine wine regions.

The issue is that new vintage top Burgundy wines sell exclusively on allocation, with increasing numbers of domaines limiting the quantities that anyone can buy. Case sizes on offer have reduced from the traditional case of 12 bottles, down to six bottles, then down to three bottles and now, in increasing instances, down to a single bottle.

Domaine Leflaive, Burgundy | © Serge DETALLE

Even if you were able to turn up with a truck-full of Benjamin Franklins, you would almost certainly only be able to spend a couple of shovelfuls and would have to back up your truck and take it home. Money won’t buy you a VIP seat when the allocation lists are drawn up. Of course, you can go to the secondary market or the auction market and try your luck there. But this is not the best strategy for purchasing wines in an efficient and cost-effective manner.

Burgundy, unlike Bordeaux, is a region based around a pyramid structure of vineyards: the Grand Crus at the top, then the Premier Crus, the village wines and, finally, at the bottom of the pyramid, the regional wines. The investment-grade wines will almost always be the Grand Crus and, in some instances, the Premier Crus, from the top or up-and-coming domaines. Unlike Bordeaux, where the vast majority of investment grade wines are red, in Burgundy, you’re just as likely to make good returns owning white wines as you are red wines.

The number of Burgundy domaines which make at least one investable fine wine today is surprisingly high. A mere decade ago, you could probably count on two hands the number of domaines whose wines you would consider for a possible investment. Today, due to a variety of factors—including the fact that the best wines from the most famous domaines have become impossible to buy and so collectors and investors have had to cast their net more widely—there are at least 30-plus domaines whose wines you would probably consider for your portfolio.

Charles Lachaux, of Domaine Arnoux-Lachaux

The blue-chip domaines include The Holy Trinity of Domaine de la Romanée Conti, Domaine Leroy and Domaine Armand Rousseau. There are also a number of other top estates to consider, such as Domaine du Comte Liger-Belair, Domaine Georges Roumier, Domaine Leflaive, Domaine Coche-Dury, Domaine Ramonet, Domaine JF Mugnier and Domaine Mugneret-Gibourg.

The rising stars of Burgundy include: the winner of the Golden Vines World’s Best Rising Star Award 2021, Domaine Arnoux-Lachaux, whose wines have gone stratospheric after winning the Award (President Macron even called to congratulate the vigneron, Charles Lachaux. Domaine Sylvain Cathiard, Domaine Georges Noellat, Domaine Jean Grivot, Domaine Duroché, Domaine Arnaud Ente, Domaine Pierre-Yves Colin-Morey and—perhaps my favorite in all of Burgundy, and the world—Domaine Jean-Yves Bizot. There are plenty more domaines that I could name with some enthusiasm.

Having travelled around 300 miles from Bordeaux north-west to Burgundy, we remain in France, as perhaps the hottest new investable wines are the Prestige Cuvées and Grower Champagnes. Champagne was historically only seen as a celebratory, non-food-related wine that was not for aging but for drinking early on at a wedding, party or an expensively purchased nightclub table.

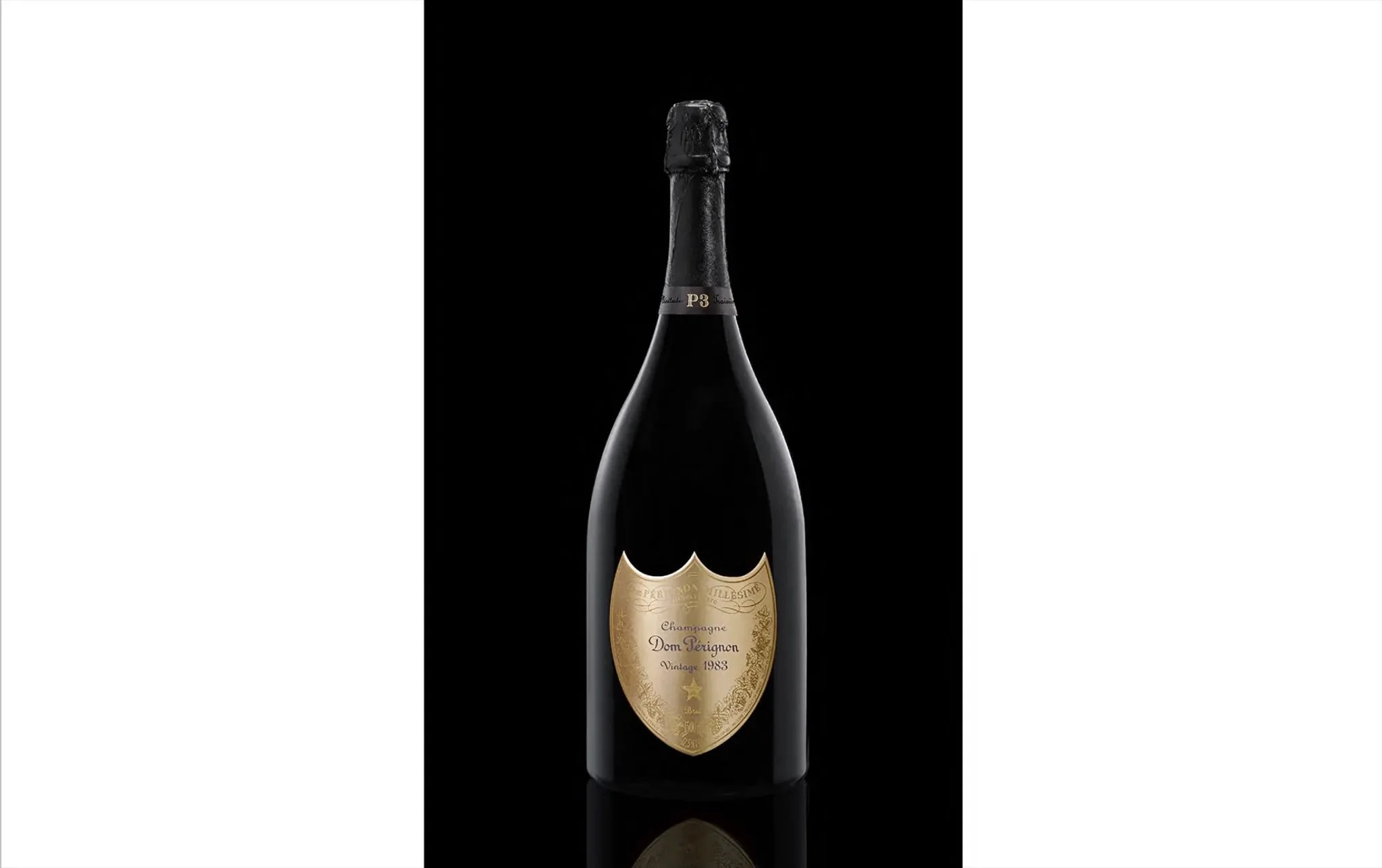

However, in the last decade or so, fine wine collectors and, in turn, investors have come to realize that the very best champagnes from the big Houses (the Prestige Cuvées such as Krug Clos du Mesnil and Clos d’Ambonnay, Dom Perignon P2 and P3, Salon and Cristal) age incredibly well, pair with many foods and have the potential for long-term price appreciation in the secondary market.

Dom Pérignon: one of the Champagne houses on which investors now train an eye | © HAROLD DE PUYMORIN

For the Grower Champagnes, the top wines from Jacques Selosse, Pierre Péters, Agrapart & Fils and Bérèche might now be considered for a small part of your portfolio. With the huge impact of social media and celebrity navel gazing, anyone who invested in Armand de Brignac’s Ace of Spades or Dom Pérignon’s Luminous range (same champagne—just luminous labels aimed at the nightclub crowd) would no doubt have a smile on their face. Indeed, if you spotted the move in Champagne early, at the bottom of the ‘J’ curve, you have made out like a bandit. We are now arguably well up the ‘J’ curve, but given these wines are still relatively accessible and affordable compared with the equivalent top still wines from Bordeaux and Burgundy there is probably still some way for these wines to go.

Outside of France, the next obvious country’s wines to invest in are the top ones from Italy. It would have been extremely difficult to have even entertained Italian wines as an investment potential a couple of decades ago. These wines were often extremely rustic, even for the table of your local trattoria. However, since then, many top producers have initiated capital expenditures programs to up their game and turn the tide.

In Piedmont, they have even changed the method of vinifying wines to make them more approachable, on the basis that most people are not prepared to wait a half century before they are ready to drink. The introduction of international grape varieties such as Chardonnay in the North and, more importantly, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc and Merlot in Tuscany (inspiring the creation of the Super Tuscan phenomena) have also been a game changer.

Bruno Giacosa in the Piedmont region

In Italy, investment-worthy wines generally come from one of three regions: Piedmont (Barolo & Barbaresco), whose wines are often seen as being more comparable in character, style and culture to those of Burgundy; Tuscany (including Montalcino) and its near neighbor, Bolgheri, whose wines are more similar to Bordeaux. However, unlike Burgundy or Bordeaux, the list of true blue-chip wineries is far shorter.

That list would include Gaja, Giacosa, Giacomo Conterno, Giuseppe Rinaldi, Luca Roagna, and—my personal favorite—Cappellano in Piedmont. You could also include Soldera, Il Marroneto and Biondi-Santi in Montalcino, and Solaia and Montevertine Le Pergole Torte in Tuscany; plus Sassicaia, Ornellaia and Masseto in Bolgheri. In the under-the-radar category, the wines from Lorenzo Accomasso in Barolo are stunning if you can find them and generally the preserve of the ‘Insider’s Insider’ group of wine-geek collectors.

We then come to the USA—or specifically, California. The issue for wine investors here is that Californian wines are generally made in small quantities, sold through an allocation list directly to consumers and seen as a bit of a local product. Whereas you can regularly find diners at Michelin-star restaurants in New York, San Francisco or Los Angeles drinking the top wines from France or Italy, it is much rarer to see the great wines of Napa being drunk in their equivalent restaurants in London, Paris or Milan.

The author at The Golden Vines Awards, aka ‘The Oscars of Fine Wine’

In the same way, although there will always be a few Californian wines to add to your portfolio, it is probably advisable to limit your selection to a few names: Screaming Eagle, Harlan, Dominus, Opus One, Colgin Cellar, Sine Qua Non and, the winner of the 2021 Golden Vines Best Fine Wine Producer in the Americas Award, Ridge Vineyards—all are some of the names that might be considered.

Best of The Rest

In the investable universe, there are remarkably few fine wines outside of the aforementioned regions. This does not mean that the rest of the world does not make fine wine. Investment grade wines are the ones that trade on the secondary market and tend to increase in price over time. Many other wines might be very fine indeed, but are not suitable for an investment portfolio.

Here are some of the wine estates that I believe might be considered for a small allocation in your portfolio. In Germany, Egon Muller and Weingut Keller; in the Rhône Valley, France, JL Chave Hermitage and Château Rayas; in Alsace, Trimbach’s Clos Ste Hune; in the Loire Valley, France, Clos Rougeard; in Austria, F X Pichler’s Unendlich Riesling Smaragd; in Switzerland, Gantenbein’s Chardonnay; in Australia, Penfolds and Henschke’s Hill of Grace. Over time, as the secondary market broadens out further, new names will, no doubt, become investment grade.

Bottle Format

This is something that needs to be discussed: as a collector, I am obsessed with large formats—over 65 percent of my collection is magnum size or above. Indeed, many wine merchant friends’ teasingly call me ‘Mr Magnum’. I love big bottles because they look great; I love serving them; the wines always age better (less oxygen per liter gets into the bottle compared with standard 75cl bottles); and, they are rarer—especially when it comes to Grand Crus Burgundy wines, which makes up the bulk of my collection.

Champagne, in particular, benefits the most from being bottled in large formats. It is just a very different, and a better, product to drink. For this reason, owning Prestige Cuvée champagnes in large formats—whether for investment or for drinking—is highly advisable. I have an outsized exposure to champagne in my collection because I absolutely adore it, and I try to avoid owning any single bottle formats (75cl) as much as possible.

The author—aka ‘Mr Magnum’—recommends larger format bottles

Elsewhere, for the fine wine investor, if you are looking for more sellable and fungible products, you would generally avoid buying large formats. For instance, selling a three-pack case of Domaine de la Romanée Conti’s Romanée Conti in 75cl bottles is likely to elicit a lot of potentially interested buyers who can price and pay for these super expensive bottles. But the same wine, in one of wine merchant Jeroboam’s London outlets, is rarer than hen’s teeth, and trying to sell that bottle at the market price in a timely fashion is nigh-on impossible.

For starters, how do you ascertain a market price for that bottle? The only place to sell it, where price discovery on that bottle makes sense, is through an auction process, which could take many months of work finding the right auction house, the appropriate auction on which to list the wine and negotiating the terms of sale with the auction house.

However, it turns out that many other collectors and, in turn, investors have worked out that large formats are the must-have fine wine collectibles and so the price premium on these large bottles for Burgundy and Champagne wines, in particular, can be two or three times as much as the standard-sized bottle equivalent. In other words, it has paid off being a wine collector and not a wine investor—because if my motivation had been investment, I would have never bought so many large format bottles.

Finally… A Word About NFTs

There is a lot of talk and media interest around the subject of non-fungible tokens despite the fact that, at least up until now, they barely register in the fine wine market. The main selling point to investors surrounds provenance (as well as rush-to-buy-induced scarcity appealing to an investor’s speculative instincts).

The provenance argument is generally bogus. An NFT does not tell you anything about how the wine has been stored, and fraud risk still exists if you end up buying a ‘fake’ NFT from an unregulated exchange or they get stolen (over US$100 million of NFTs have been the subject of theft in the first half of 2022, according to the London Times). The reason why ‘in bond’ storage is so important is that it gives the investor a very real sense of provenance, both in terms of how the wines have been stored and how the wines came into bond in the first place. Outside of the bonded system, purchasing an NFT is potentially better than buying wines where you have no real idea where they came from (the chain of title can be ‘muddy’) and how they were stored.

Domaine Mugneret-Gibourg, Burgundy

In many existing NFT markets, there have been many strongly rumored instances of price pumping: when an NFT is ‘struck’ with this phenomenon, the price suddenly jumps higher and higher as buyers’ bids hike up the price. The ‘pumping’ is often rumored to have been done either by the seller himself, a connected party or someone who has an economic incentive to pump the price (that’s right: it’s often not even a ‘real’ price). At some point thereafter, when the market establishes a real price for the NFT, the price will fall off a cliff back to—or even below—the issue price. For this reason, NFTs should come with a health warning on them (like many crypto assets), and you should tread with extreme caution.

The real benefit of NFTs, when it comes to fine wine, is actually not for the investor but for the wine producer. Those who have been involved in NFT issuance are often the ones who are fed up with seeing their wines soar in the secondary market without them benefiting from any of the upside. When an NFT is traded, a portion of the selling price will go back to the wine producer (additional ‘slippage cost’ for the investor). If the NFT is traded multiple times, the money coming back to the wine producer can become meaningful. This is great for the wine producer, but not so great for the investor, who bought it on the promise of some spurious pitch about provenance.

For NFTs to become compelling, they will need to come with more added value attached to owning them. For instance, future allocation rights to purchase wines; membership of a fine wine club; VIP visits to the winery and other ‘money-can’t-buy’ wine experiences. David Garrett’s Club dVin has embedded some of these benefits into his NFT program.

When it comes to fine wine as a pure investment product, though, I am just not convinced.

Watch this space for Part III—all about avoiding the pitfalls inherent in investing in fine wine.

Lewis Chester DipWSET is a London-based wine collector, member of the Académie du Champagne and Chevaliers du Tastevin, co-founder of Liquid Icons and, along with Sasha Lushnikov, co-founder of the Golden Vines® Awards. He is also Honorary President and Head of Fundraising at the Gérard Basset Foundation, which funds diversity & inclusivity education programs globally in the wine, spirits & hospitality sectors.

Read an original version of this article on The Robb Report’s official website here.